2021: Year 9 & 10 Category: Winner

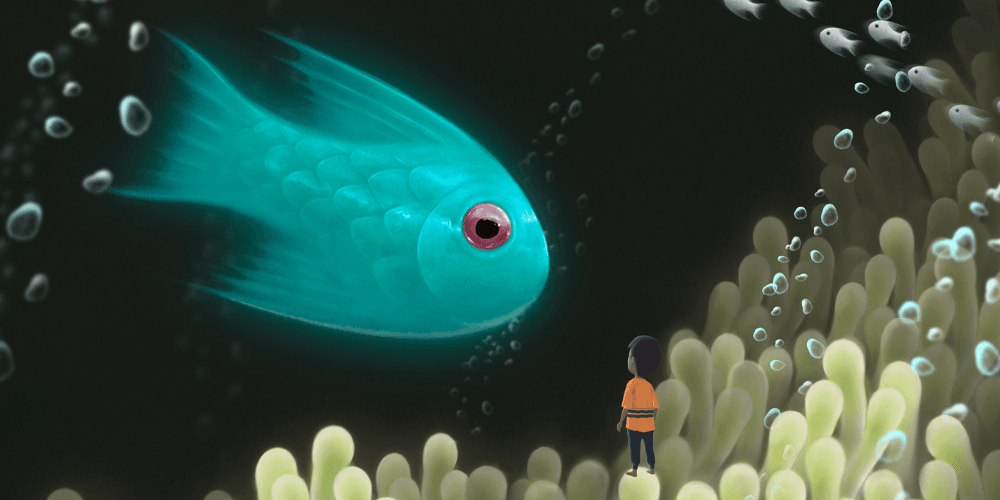

Blue All the Way Down

by Matilda Jenkins, Alfred Deakin High School

The sea was so salty you could float in it, face down, and it looked like you were dead.

They said it was from the tears of a goddess. When it rained you could see that the drops were translucent, clouded with almost indiscernible particles of salt. The people who lived by the sea wrung out the rainwater in muslin cloths to purify it. When the cloths dried stiff and grainy, they were vindicated; there was satisfaction in a myth fulfilled. There was satisfaction in a god appeased, or, as they thought, outsmarted.

There was a boy in the sea. He had once lived on the shore, with his mother. She dressed in black now but he only felt a little guilty. He was happy in the ocean.

The boy used to taste the rain as it fell from the sky. It wasn’t until later that he realised that the rain wasn’t tears at all, or even a brine. That was after, though. He had been immersed in it too long by then to know the difference anyway.

The boy did not have many friends. He had a sardine called Oskar. He built the fish a wheeled tank out of an old copper wagon and a glass bowl, and everywhere he went, there was the clack-clacking of the patinated contraption.

The shattering of the glass was inevitable; the town had been holding its collective breath for it since the beginning. But when it came, no one was around to see. The boy was miles out of town. He snatched the fish up, along with several shards of glass, and ran home. When he arrived, both the fish and his hands were marred by streaks of oxidised blood. Although his mother gathered him quickly into her arms, sensing his distress, she was too late. He refused to relinquish the fish.

Eventually, she brought him a locket and told him to keep the dead fish in it. The townsfolk tsked and clucked, shaking their heads at the modern ways of this feckless, reckless young woman. “In my day,” they said, and waxed eloquent about discipline, waving their arms in the air as if they didn’t understand.

The death of the fish would not ordinarily have mattered to a boy, but to this one it was everything. He could not express in words the world he had lost in that fishbowl; the hours of comradely contemplation; the solitude and the company.

His mother decided, after his hands had healed but his heart was still broken, that something must be done about the locket. She felt it was wrong to encourage such morbid fascinations as her child was exhibiting.

He didn’t take the locket off even to sleep, but he slept just as if he were dead, and she crept in and stole away the dead fish as he was dreaming. She buried it in a distant corner of their garden underneath the thorny rosebush.

The next day, she saw that from the boy’s hands welled small droplets of blood, and his fingernails were caked with dirt. In the backyard, there was a neat hole, and no fish to be found. The young mother looked on at her child, fingering his locket, and decided at last that to separate him from the fish would be not only cruel but impossible.

After, there was peace for a time, but the boy never gave up the locket, choosing instead to hide it beneath his shirt. The smell eventually dissipated as rotting flesh gave way to yellow bone, and they were happy. They went to the beach; the boy liked to bob up and down on the waves. He could feel the tickle of fish sweeping past him if he stayed still enough, and he thought of his sardine and smiled.

It was almost a year after the fish incident that the mother met a young man and fell in love. He was a fishmonger from a neighbouring town, the possessor of eyes as bulging as those which he scooped from their sockets, day in and day out, as he filleted his wares. But his arms were muscular and his smile enchanting, and he looked the young woman in the eye as he spoke to her.

The love grew slowly but surely between them, snaking its red and green tendrils around their guts, feeling and prodding until the pressure grew too great and they were forced to give in. Suddenly, when the boy went to the beach, he went with his mother – and he went with the fish-murderer.

Perhaps it was the image of his hands, bloodstained and broken by the glass, and of Oskar, his one true companion, lifeless in his palms, which made him hate the fishmonger. Perhaps it was his innate fear of change, for the boy was as much animal as he was human, and lived instinctually, shying away from reason and rationality.

Whatever it was, his hatred broiled and bubbled and, as always, boiled over. He was like a river that threatened to burst its banks. Prior to the fishmonger and his bulging eyes, the mother had lived in constant fear of his swirling waters. Now she was floating as if the water were as salty as the sea in which they swam every summer.

The boy, dressed in threadbare shorts and shirtless, walked ahead of his mother now. They had once strolled hand-in-hand towards the waves, but now a stranger was holding his mother’s hands. Where once there had been resentment, now simmered undiluted jealousy, its bile burning a hole in the base of the boy’s gut. He felt it resonating through his collarbone, his thorax, the base of his spine.

He ran into the water and reached back, expecting the brush of his hands against his mother’s, but his hands slipped through the frigid air.

His mother was behind him, the boy knew it. He was determined not to look at her; she had to look at him. But his mother was staring into the bulging eyes of the fish-murderer. She would not see him.

The sea was so salty you could float in it and it looked like you were dead. The boy knew this; he looked around him and saw the other boys his age doing it. The first few times raised whispers of concern from onlookers, even prompted a dramatic rescue once to peals of laughter from the boys; but after, bystanders would simply roll their eyes and look away.

The boy who was maybe half fish by then, but not completely, stepped onto the sand, bones thrumming with envy. He slipped into the water silently and it felt different this time, as if he had merged with the waves, and he was slippery now. He looked back to the shore and stared at his mother and her companion’s big bulging eyes. He saw that she was the only one for whom he was staying onshore, and she had someone else now. Maybe she didn’t need him?

He flipped, still maybe a little boy in shredded shorts bobbing atop the waves. He looked down into the water and saw that it was blue all the way down. He yearned for that deep blueness, but he knew he must wait a while longer if he was to descend.

The sea was so salty you could float in it and it looked like you were dead. But were you really dead when you were a part of the sea? The boy’s mother was kissing the fish-murderer, enemy of the sea, on the sand. It slipped between her toes and she was at last happy. She did not think of her child.

A strand of seaweed caught on the button of the boy’s shorts and he smiled. He knew that with every breath he took, he drifted further from shore. He didn’t mind. He saw it now; his mother didn’t need him.

What followed was indescribable.

His mother left him there, in the ocean. She knew that he belonged with the fish. With the waves.

She cried and dressed in black, the young mother. But somewhere there was relief; freedom from the strange oppressive being who came into her life so suddenly. For when she had given birth, her stomach was flat and he slid into the world without a push, on a gush of salty water.

Eventually, the young woman was happier than before. The fish-murderer smiled at her and his bulging eyes were safe and comfortable. They had another child who was rosy, plump and made friends with the other children in the village. Soon, the strange boy in the ocean was a distant memory.

She still cried sometimes, after the idea of him, but she was happy.

His green body floated somewhere in the ocean, and he was happy too. Sometimes he cried, at the idea of her, but then he felt Oskar the sardine brushing past him and forgot. He was better off a fish.

JUDGES’ COMMENTS

With a sophisticated and original concept handled well, this piece is excellent. The writer demonstrates outstanding use of language with evocative imagery and repetition of the opening sentence to underpin the narrative’s structure. She also makes interesting observations about humanity and the ocean, plus refreshingly unique and slightly unsettling themes to make the reader think.